When the Philippines was handed to the “great” American nation whose torch and broken chains became a monument of freedom and human rights, its people did the same for the Filipinos. Gat José Rizal’s secular martyrdom was first immortalized on December 20, 1898 when First Philippine Republic President Emilio Aguinaldo declared the 30th of December of every year as a “national day of mourning for Rizal and other victims of the Spanish government, throughout its three centuries of oppressive rule.” In 1901, under the American Civil Governor William Howard Taft, Rizal became the nation’s foremost hero even without formal legislation. His heroism is never a question as the Filipino revolutionaries welcomed him and his principles with fervent salute; although the Americans probably saw it more as an opportunity to plot their conquest through it. Regardless of the differences in their aspirations, the Filipinos and the Americans only had one aim in mind—to pay tribute to Rizal.

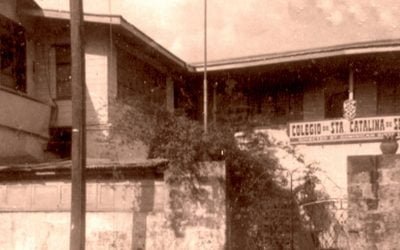

Several other measures concerning the iconization of Rizal were taken by the Americans. On September 28, 1901, Luneta was granted to be the site of Rizal’s monument that would also be his final resting place. Luneta witnessed the desperation of the Manila high society to rub elbows with their Spanish conquistador, as well as the ruthless deaths of those who dared to betray Spain, including Rizal. The committee-incharge—which consisted of Pascual Poblete, Paciano Rizal, Juan Tuason, Teodoro Yangco, Mariano Limjap, Máximo Paterno, Ramón Genato, Tomás del Rosario, and Ariston Bautista—opened an international design competition for the sculptors of the West from 1905 to 1907. The judging committee—composed of Governor General Frank Smith, John MacLeod, and Dr. Maximo Paterno—announced the winners in a press release on January 8, 1908. Out of the 40 entries submitted and of the 10 shortlisted, the boceto (small scale design) of Italian Carlos Nicoli titled “Al Martir de Bagumbayan” (To the Martyr of Bagumbayan), was granted the top prize. It was an 18-meter tall grandiloquent neoclassical work—its corners were guarded by lions and lampposts; its lower base in two shades of white Carrara marble; its die in two shades of grey of the same marble wreathed with allegorical figures of Victory, Justice, Fine Arts, and Music; at its peak was the statue of Rizal with the Angel of Fame drifting over him. Despite its being arguably the most beautiful Rizal monument that the Philippines could have had, it did not take into account the natural calamities and the budget. Ideally, the materials should be sourced locally and should be within the Php100,000 budget, including the prizes for the winners. The contract was ultimately awarded to the runner-up, Swiss Richard Kissling’s “Motto Stella” (Guiding Star). Although it never materialized, Nicoli’s design became the inspiration behind the Rizal Monument of Biñan—lions guarding by the entrances of the original concrete fence, lampposts carried by women at its corners, and allegorical figures of women on each side of the third base. The oldest in Laguna and once the second largest in the Philippines next to the one in Luneta, the monument was completed on May 14, 1918.

Biñan’s Rizal Monument has markers affixed on each of the four sides of the die. One of these is addressed to the Biñanenses, a challenge to fulfill their duty, “Al Dr. Jose Rizal el pueblo de Biñang en cumplimiento de su deber.” Included also are portions of two of the most important ideas Rizal penned in Spanish. One was from his Noli Me Tangere (1887), spoken by Elias before succumbing to his fatal wounds: “I die without seeing the dawn brighten over my native land. You, who have it to see, welcome it, and forget not those who have fallen during the night.” The other was from one of Rizal’s most important letters dated June 20, 1892 as he expected to be sentenced to death upon returning to the Philippine shores. He wrote: “I wish to show those who deny us patriotism that we know how to die for our duty and our convictions. What matters death if one dies for what one loves, for native land and adored beings?”

The original statue of Rizal, believed to have been created by National Artist for Sculpture Guillermo Tolentino, was facing the west and towered over the entire town plaza of Barangay Poblacion. But on September 22, 2015, to much sadness of the Biñanenses, a lightning decapitated the statue. Its wreckage is kept in the City Museum. In 2016, worldrenowned sculptor Frederic “Fred” Caedo created a replica, which found its way to the top of the monument. Caedo also restored the blasted original work, and the restored Rizal statue now stands in its new home across the City Hall of Biñan in Barangay Zapote. On May 14, 2018, a hundred white balloons were freed to reveal the marker that celebrates the monument’s one hundred years. Then, green balloons filled with gratitude were released to convey what was in the hearts of Rizal’s fellow Biñanenses as the city treats the national hero as its very own son.